Thursday, November 08, 2007

Healthcare Financing in the Developing World: Is Nigeria’s Health Insurance Scheme A Viable Option?

The idea of a National Health Insurance Scheme was first considered by the authorities in 1962 but successive governments lacked the political will to actualize this dream. It was not until 43 years after when the immediate past President, Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, set apart the sum of 26 billion Naira for the scheme in the 2005 budget. The former president directed at that time that no deductions be made from any government employee until the end of 2006 when the performance of the scheme would have be evaluated. He opined that this grace period would allow for confidence building. His speech at the launch of the program in June 2005 attempted to debunk the widespread cynicism been exhibited by majority of Nigerians about this typical Nigerian white elephant project.

The Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) was established by Decree No 35 of 1999. The Decree states that “there is hereby established a scheme to be known as the National Health Insurance Scheme (in this Decree referred to as "the Scheme") for the purpose of providing health insurance which shall entitle insured persons and their dependants the benefit of prescribed good quality and cost effective health services as set out in this Decree”.

The NHIS decree statutorily allows each insured person to decide which health centre he wishes to register with. A monthly capitation is paid to the health centre from the pooled funds. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) are empowered to coordinate the activities of the health centers as they dispense healthcare to the insured while the over-all regulation of the scheme rests with the National Health Insurance Scheme Council. The council was established by the same decree.

The WHO has this to say about healthcare financing in Nigeria: “Funding Health in Nigeria is from a variety of sources that include budgetary allocations from Government at all levels (Federal, States and Local), loans and grants, private sector contributions and out of pocket expenses. The value of private sector and out of pocket expenditure contribution to financing the sector is yet to be determined. According to a World Bank source, the public spending per capita for health is less than USD 5 and can be as low as USD 2 in some parts of Nigeria. This is a far cry from the USD 34 recommended by WHO for low-income countries within the Macroeconomics Commission Report. Although Federal Government recurrent health budget showed an upward trend from 1996 to 1998, a decline in 1999 and a rise again in 2000, available evidence indicates that the bulk of recurrent health expenditure goes to personnel. Federal Government recurrent health expenditure as a share of total Federal Government recurrent expenditure stood at 2.55% in 1996, 2.96% in 1997, 2.99% in 1998, declined to 1.95% in 1999 and rose to 2.5% in 2000. Beyond budgetary allocations, a concern in funding the health sector in Nigeria is the gap between budgeted figures and the actual funds released from treasury for health activities”.

The Nigerian NHIS is already facing some problems. Some segments of the populace are left out. Recently, retired senior citizens complained on national television that the scheme does not cater for them. There is the issue of integrating the rural populace who do not have clearly identifiable sources of income since their means of livelihood is mainly subsistence farming. There is also the problem of inadequate human capacity to drive the NHIS. There is still a dearth of necessary professionals grounded in healthcare financing whose input cannot be done away with. And how will the NHIS survive if we do not deal squarely with the recurrent problem of graft? And graft manifests in different ways: from the healthcare provider who does not make essential medicines available or provides poor quality service, to the HMO who deliberately delays/withholds captitation. Many of the consumers grapple with the bottlenecks associated with accessing healthcare under such an administratively cumbersome scheme. Perhaps the greatest problem facing the NHIS is the monopoly it enjoys as lack of competition stifle growth and birth mediocrity. The success recorded in the telecommunication industry in Nigeria so far has been attributed in part to the vigorous competition it is experiencing. Many are already calling for the liberalization of the health insurance business as obtainable in some developed economies.

The foregoing clearly lends credence to the fact that for sustained development in the healthcare industry in Nigeria and the developing world, healthcare financing must not be left in the hands of government alone; certainly not in the hands of inept, pathologic, corrupt governments. It is in this vein that many have proposed other funding options including the somewhat ‘extreme’ idea of wrenching the NHIS from the hands of government lest it goes the way of other public enterprises such as the National Housing Fund, National Provident Fund, and many defunct Pension Schemes.

We should begin to promote the commercial health insurance option as this will bring some life into the health insurance industry in the developing world. Informal prepayments arrangements as is the case with some rural cooperative societies such as Country Women Association of Nigeria (COWAN) have been proposed as an attractive model for low income urban/rural populations in the informal sector since this eliminates the high cost of premiums necessary to subscribe to commercial health insurance. The downside to this model is that the fee-for-service approach may compromise the quality of service provided by healthcare providers. It is also very likely that the amount contributed by these poor families may not be adequate to cater for major illnesses.

Before the developing world finds her feet, donor countries/agencies can explore the possibility of setting up not-for-profit Voluntary Health Insurance Plans (VHPs) which has great potentials for mitigating the numerous health problems of the poor.

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

Paul Farmer: The Man Who Would Cure The World

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Tracy Kidder, described Paul Farmer as "a man who would cure the world". I found the following brief bio about Dr Farmer on Harvard Medical School's website: "Medical anthropologist and physician Paul Farmer is a founding director of Partners In Health, an international charity organization that provides direct health care services and undertakes research and advocacy activities on behalf of those who are sick and living in poverty. Dr. Farmer’s work draws primarily on active clinical practice (he is an attending physician in infectious diseases and chief of the Division of Social Medicine and Health Inequalities at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston, and medical director of a charity hospital, the Clinique Bon Sauveur, in rural Haiti) and focuses on diseases that disproportionately afflict the poor. Along with his colleagues at BWH, in the Program in Infectious Disease and Social Change at Harvard Medical School, and in Haiti, Peru, and Russia, Dr. Farmer has pioneered novel, community-based treatment strategies for AIDS and tuberculosis (including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis). Dr. Farmer and his colleagues have successfully challenged the policymakers and critics who claim that quality health care is impossible to deliver in resource-poor settings".

I consider him a great inspiration.

Friday, November 02, 2007

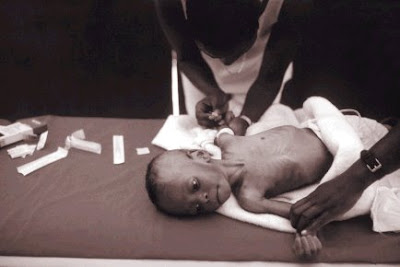

Caesarean Birth at Evangel Hospital

ECWA Evangel hospital trains Family Medicine residents to dispense care and solve common health problems that are common to most people in most places with the most cost-effective approaches. The ability to be able to rapidly carry out a Caeserean delivery is one of the fundamentals of emergency obstetric care. The video is one of several deliveries carried out regularly by the highly competent personnel at Evangel Hospital. Take a peep!

Just rearranged this blog!

Post your comments/suggestions about this to my mailbox. Thanks!

Friday, October 05, 2007

The Millennium Development Goals: counting down to 2015

In September 2000, 189 Heads of State adopted the UN Millennium Declaration. It was a roadmap setting out goals (Millennium Development Goals) to be reached by 2015. There are eight goals, 18 targets and 48 indicators to measure the MDGs. Three out of the eight goals and eight of the 18 targets relate directly to health. These are:

· Goal 4: Reduce child mortality

· Goal 5: Improve maternal health

· Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases.

Targets related to the goal of combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases are:

· Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

· Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other serious diseases.

How far have we gone down the road towards achieving these goals with just eight years left to that all-important deadline?

There has been some progress. However, nearly 11 million children under the age of five die every year globally. In 16 countries, 14 of which are in Africa, levels of under-five mortality are higher than in 1990. More than 500,000 women die in pregnancy and childbirth each year and maternal death rates are 1000 times higher in sub-Saharan Africa than in high income countries.1

A growing awareness of malaria’s heavy toll, matched with a greater commitment to curtail it has helped to spur key malaria control interventions, particularly insecticide-treated net use and access to effective antimalarial drugs. Resistance has now developed to all classes of antimalarial drugs except artemisinin and its derivatives. When used correctly in combination with other antimalarial drugs, artemisinin is nearly 95% effective in curing malaria. The rationale is that when two drugs with different modes of action are given simultaneously they attack different targets in the parasite. If a mutation should occur to make the parasite resistant to one of the drugs, the second drug will kill it.

In just four years (1999-2003), distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets increased 10-fold in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite this progress, urban dwellers are six times more likely to use the nets than their rural counterparts, according to data available from a number of countries in the region. Similarly, the richest fifth of the population are 11 times more likely to use them than the poorest fifth.2

There were an estimated 8.8 million new tuberculosis (TB) cases in 2005, including 7.4 million in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. More than 1.6 million people died of TB, including 195,000 patients infected with HIV. The number of new tuberculosis cases is growing by about 1% per year, with the fastest increases in sub-Saharan Africa. More ominous has been the emergence of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB).1, 3, 4

Fortunately, it has not been all doom and gloom. Recently comes a World Bank Report which states that the AIDS pandemic is on the decline in countries such as Rwanda, Uganda and Ethiopia. The infection in West Africa has not reached the high levels it was feared that it might reach. It cannot also have been bad that the recently concluded G8 summit at Heiligendamm, Germany promised $60 billion dollars to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS and other diseases affecting Africans.

Certainly with the right combination of commitment and aid, there is still enough time to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2006; New York, United Nations June 2006.

2. Year in Review 2006. Geneva; World Health Organization 2007.

3. Global Tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. WHO report 2007. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2007 (WHO/HTM/TB/2007.376)

4. Raviglione MC, Smith IM. XDR Tuberculosis- Implications for Global Public Health. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (7): 656-9.

*Dr. A. Onu is of the Department of Family Medicine of the Jos University Teaching Hospital and Editor-in-Chief of the Jos Journal of Medicine. This piece is the editorial of the current issue of the Journal. I am an Associate Editor of the Journal.

Tuesday, September 18, 2007

Where AIDS Efforts Lag

By Lola Dare, Jim Yong Kim and Paul Farmer

President Bush made a historic pledge in his 2003 State of the Union address: to get urgently needed AIDS

treatment to 2 million people living with HIV in impoverished countries by 2008. Congress concurred and

launched a major initiative to fight AIDS focusing on 15 developing nations. At a U.N. General Assembly

conference on AIDS this year, the United States went further and committed, along with other countries, to come

as close as possible to universal access to HIV treatment by 2010.

We have come a long way since 2000, when AIDS treatment was available to only the fortunate few. Activists

campaigned successfully to drive down the cost of treatment with affordable off-patent AIDS medicines that are

now available in most developing countries. After initial objections, the U.S. government became a major

purchaser of generic drugs.

But now that donor governments are providing more funding and medicines are becoming available, a new

bottleneck threatens the success and sustainability of the effort. People with AIDS in Africa are dying simply

because there aren't enough nurses, doctors and pharmacists to administer treatment. Without a new effort to

train, retain and support health workers in numbers sufficient to meet basic needs, the United States will not be

able to keep the deal it made with Africa in 2003.

It takes years to graduate a new doctor or nurse, and most of them prefer to build a career in a major city with

well-equipped hospitals. But with modest investments, donor governments can quickly empower and mobilize an

army of health workers made up of the hundreds of thousands of unemployed or underemployed people living in

the very settings where HIV's toll is heaviest. Women in particular are often already serving as caregivers at the

community level, usually without training or compensation.

Starting in Haiti's central plateau, the organization Partners in Health has trained and employed hundreds of

accompagnateurs, or health companions, across the group's projects in five countries, including the United States.

Accompagnateurs are paid a stipend to provide a broad range of services, including drug distribution, disease

observation and reporting, clinical referrals, and the social support that people with chronic illness so often need.

This modest investment is, we believe, one of the chief reasons that adherence to AIDS therapy is so high within

our projects -- and why death rates are so low.

Community health workers are lay people on the front lines who provide effective health services and support in

countries reeling from AIDS. These nonprofessionals -- often living with HIV themselves -- are rooted in their

communities, can be trained quickly and are less likely to emigrate in search of better wages and working

conditions. They have deep knowledge of their communities, where they are familiar and trusted neighbors. With

continuing training and support, they can rapidly form a strong and active force filling deadly gaps in health

personnel and services.

Many programs have sought to rely on "volunteers" and deny these laborers pay for their services -- a model

conceived in wealthy countries. But in poor countries this amounts to exploitation of the poorest to treat the

sickest. It should be replaced by programs that ensure living wages, continuing training and a career path.

Community health workers cannot succeed alone; they are not an excuse to cut corners. Professional backup

from doctors, nurses and medical officers is necessary to provide supervision and to treat referrals. But the pool

of available health professionals in many African countries is too small to address basic primary-care needs and

far from adequate to supply new donor-sponsored global health programs.

Unintentionally, the laudable U.S. efforts to fight AIDS and malaria in Africa can end up weakening primary

health systems that are already crumbling by hiring doctors and nurses away from public clinics and hospitals

where they are also desperately needed. When primary public health systems fail, disease-specific initiatives will

also fail. The United States must get serious about increasing the overall supply and retention rates for health

professionals in sub-Saharan Africa.

According to World Health Organization estimates, the U.S. share of the global cost of training and supporting a

healthy workforce sufficient to meet internationally agreed-upon targets in sub-Saharan Africa is roughly $8

billion over five years.

On this World AIDS Day, we must match the audacity of President Bush's 2003 pledge with a complementary

initiative for training and keeping enough new health professionals and community-level workers to fulfill the

promises the United States has made.

Article from The Washington Post, Friday, December 1, 2006; Page A29

Lola Dare is executive secretary of the African Council for Sustainable Health Development International. Jim

Yong Kim and Paul Farmer are co-founders of Partners in Health International; both teach at Brigham and

Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

Tales from West Africa

Her lexical prowess will bow you over! You will also discover that she is not afraid to be vulnerable as she blogs from the heart.

You can access the blogs at http://www.jankwanomedic.blogspot.com/ andhttp://www.saralynnnege.wordpress.com/

Thursday, September 06, 2007

Winning the War against HIV/AIDS: Involving Community Health Workers

Several studies have already established the place of CHWs in the war against HIV/AIDS. I stumbled on a WHO document recently which is a must-read for everyone involved in this war.

We can no longer wait for PLWHA/PABA to come to us. We must go into the community and look for them. We must be proactive. And we cannot do this effectively without the CHWs.

Please read the WHO's document on CHWs at this link www.who.int/whr/2004/chapter3/en/index5.html

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

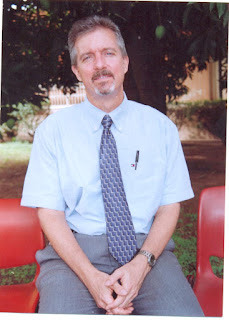

Dr Tom Thacher goes to Mayo Clinic

I thought about this post for a while before writing. I especially was concerned about the fact that Tom may not approve. Yet, I found it difficult to resist the urge to write about a man who is many things to many people. I eventually came up with a short write-up, adopting a middle-of-the-road approach.

I thought about this post for a while before writing. I especially was concerned about the fact that Tom may not approve. Yet, I found it difficult to resist the urge to write about a man who is many things to many people. I eventually came up with a short write-up, adopting a middle-of-the-road approach.In an earlier post, I discussed the importance of the discipline of Family Medicine as the panacea to the problem of health access in resource-poor settings suggesting the need for a paradigm shift from heavy spending on tertiary institutions to increased budgetary allocation to ensure sustainable primary care development. I had earlier raised the issue of inadequate human capacity, among others, pointing out that for resource-challenged settings to succeed in their bid to improve their health outcomes, they must train and retain healthcare workers who will not only dispense quality primary care but also embark on research that directly impart the people and provide patient-oriented evidence that matters.

There is someone who has played a key role, albeit quietly, in the forgoing for the past 20 years in Nigeria. He is Dr Tom Thacher.

He came to Nigeria as a missionary after completing his residency in Family Medicine in the United States about 20 years ago. He established the department of Family Medicine and Informatics at the Jos University Teaching Hospital after working in some other centers. He started with the training of four residents but at the moment, there are 25 residents in the department. Many of the early residents have graduated and either gone on to become trainers in other centers or taken up positions of responsibility in Nigeria’s health industry.

Tom was the director of research at the Jos University Teaching Hospital. He provided guidance for specialists in other disciplines and supervised residents’ dissertations. He conducted groundbreaking studies in rickets and researched into common killer diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. I read a copy of a Liverpool University PhD thesis on tuberculosis he supervised. He insists that research done in any community should impart the people.

Tom promoted the place of medical informatics. He recently supervised the creation of a database for entry of all patients’ data seen at the department of Family Medicine of the hospital. The department attends to more than 35,000 patients annually.

Tom is strict and disciplined. Pasted in a conspicuous place in his office is this inscription: “Your lack of planning is not my emergency”. He is an avid reader and a time manager. He leads by example, something rare in this society. We who followed had no option than take a cue. He is content, never showy, almost austere. In spite of his many achievements, his published papers, his pedigree, he remained simple, humble.

He insists on excellence. He supervises my dissertations for the faculties of Family Medicine of the West African College of Physicians and the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria and demands no less from me.

Dr Tom Thacher’s life in Nigeria cannot be fully elucidated here: it is for another place, for another time.

He now joins faculty at the prestigious Mayo Clinic in Rochester, USA.

Thursday, April 12, 2007

The Emergence of XDR Tuberculosis: Implications for Public Health in Resource-limited Settings.

XDR tuberculosis, classified as cases that are resistant to three or more of the six second-line drugs for the disease, has a mortality rate of more than 85%. This is not altogether a new occurrence as XDR tuberculosis was first described more than a decade ago.

XDR tuberculosis is not the same as multi-drug resistant (MDR) tuberculosis. In the latter, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has become resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin.

South Africa is at the moment trying to contain an outbreak of XDR tuberculosis which has spread to all the country’s provinces. The WHO is sending a permanent staff to that country to help with the containment effort. The resistant strain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis is said to have originated from the KwaZulu-Natal province. Experts are of the view that XDR tuberculosis has spread beyond South Africa citing the lack of adequate diagnostic capacity and poor notification mechanisms as the reasons why the outbreak is being under-reported by other countries. Mario Raviglione, director of Stop TB at WHO refers to the outbreak as an absolute emergency lamenting that the world is not responding quickly enough. A US$95 million dollar appeal made in Paris last October to combat this emerging threat has met little response.

We all know that the very existence of XDR tuberculosis is an indictment on our health systems since it reflects weaknesses in tuberculosis management which otherwise should minimize the emergence of resistance. Early, accurate diagnosis and timely institution of the appropriate curative regimen which are monitored for adherence are important steps in tuberculosis control. When drug regimens and tuberculosis control are sub-optimal, drug-resistant strains are selected which eventually proliferate and with repeated treatment errors, multi- and extensively-drug resistant strains are born.

Chances are that in most resource-poor settings, the scenario I painted above about tuberculosis management and inefficient health systems is often the rule rather than the exception. It follows then that if the status quo remains, tuberculosis might go beyond what we now know as XDR tuberculosis.

There is no easy panacea to this threat. But the panacea does exist; we must be ready to pay the price. Who wants to experience the torment of tuberculosis becoming an incurable disease?

Resource-poor settings need an effective disease control infrastructure beginning with strengthened rapid diagnostic capacity which is accessible and can be deployed at the point of care. This should be supported with unlimited access to quality first- and second-line drugs with mechanisms put in place to ensure adherence. Preventing spread is a challenge but it is doable. Special attention needs to be paid to the immune-suppressed patients because of their vulnerability. All HIV patients should be screened regularly for latent tuberculosis and antiretroviral drugs should not be delayed unnecessarily. As a matter of urgency, resource-poor settings must have access to drug-susceptibility testing which at the moment is mainly found in developed societies. The place of increased surveillance and research bordering on TB control cannot be overemphasized. And I suggest we hurriedly form enduring partnerships designed to urgently enhance the production of third line drugs which the world is taking lightly now.

Monday, March 26, 2007

In the Spirit of the Doha Declaration

How come then Novartis instituted a lawsuit against a company in India for producing generics of the anticancer drug, Glivec? The generic costs about $2,700 yearly per patient while Glivec costs $27,000 for the same time period.

Pfizer is fighting the Philippines government for approving a generic of the antihypertensive, Norvasc. The generic costs 90% less.

Oxfam International released a report recently stating that rich countries have broken the spirit of the Doha Declaration (see www. Oxfam.org for a copy of the report, Patents versus Patients: Five Years after the Doha Declaration). The report states that many wealthy countries go to great lengths to protect medicine patents putting profits before patients. As a result, patented medicines continue to be priced out of the reach of the world’s poorest people.

It is instructive to remember that the burden of disease continues to rise especially in poor countries. For instance, between 2001 and 2005, more than 4 million people became newly infected with HIV in developing countries. Yet, 74% of AIDS medicines are still under monopoly, 77% of Africans have no access to AIDS treatment and 30% of the world’s population does not have access to essential medicines.

In the spirit of the Doha Declaration, the Oxfam report concluded with some recommendations which I agree with and summarize in my own words below:

1. Wealthy countries should live up to their promise and relax the strict intellectual properties laws as regards patented medicines.

2. Rich countries should muster the political will to provide technical support that will enhance universal access to essential medicines

3. Leaders in developing countries should become responsible and explore, with a view to invoking, the “public health safeguards written into the WTO’s intellectual property rules” in order to abolish differential access to medicines.

4. Pfizer and Norvatis should, if not in the spirit of the declaration, for the sake of corporate social responsibility, end their feud with developing countries.

Thursday, March 22, 2007

His Excellency’s ludicrous Elixir for AIDS

I was flustered by the claims being made. I still am.

His Excellency, the President of the Gambia, Yahya Jammeh, had invited the CNN team to come and see the wonders being wrought by an herbal concoction he had personally formulated for the treatment and cure of AIDS. The constituents of the concoction were revealed to him in a dream!

Many Gambians have already abandoned their HAART for this miracle cure and the risk for resistance will certainly skyrocket because many antiretroviral agents are unsparing.

CNN’s repeated efforts to interview the president failed and attempts to subject the concoction to standard scientific testing met a brick wall. An expatriate who spoke out against the president’s farcical claims was thrown out of the country within 48 hours. Even more disheartening is the fact that the health minister, a physician trained in the West, swore on set that the concoction can cure AIDS.

What is wrong with Africa?

Why has his Excellency forgotten so soon similar claims made by Thabo Mbeki and the former South African health minister? Did his Excellency ever hear of Nigeria’s Dr Abalaka? Why return to ideas and claims that belong in the Stone Age? Why belittle the threat of a scourge currently devastating us, the world’s poor? Why would the Gambia, a country with a Medical Research Council which is home to prolific, world-renowned researchers drag Africa backward in her quest to see the end of AIDS?

Why?

Thursday, February 22, 2007

Meet Ron Brittan

Few legal practitioners there are who render services for free. And we cannot castigate those who charge fees: it is just the way things go; commerce, among others, drives society.

Certain individuals, however, have gone above the norm, above our basic human egocentric tendencies. Such individuals extol our communality. Such persons, like Ron Brittan, possess large hearts.

I refered a friend who was in dire need of legal assistance to Ron recently who rendered help promptly, free of charge. This same gesture he has extended to other acquaintances in the past, rationalising that this is his modest contribution to bridging inequality and promoting equity for poor communities.

Ron Brittan, a legal practitioner, immigration activist and social worker who resides in Oxford, England, wrote the following lines to me recently..........."Dear Joseph:

I checked out your blog and found it extremely interesting. I wish you every success in achieving your noble objectives.

I too am concerned with the Millennium Goals, especially as far as Nigeria is concerned. I try to make a small contribution by assisting young people to come to UK to study, and to get work experience, so as to return to their country with enhanced skills. Your friend Andrew is a case in point.

Most of our leads come from Rotary and Rotaract clubs in Nigeria, through a programme initiated by the Oxford Rotary Club. Notably, many members of Jos Rotaract club have participated.

Hope to hear from you again, and we may possibly be able to pool some ideas.

Ron Brittan,

Immigration Link (An Oxford charity)".

His webpage www.geocities.com/ron_brittan/index.html is even more revealing.

This post is an ode to Ron!

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

Human Resources Development For Health: Key to Achieving Millennium Development Goals.

Human Resources Development For Health: Key to Achieving Millennium Development Goals.

The great majority of Nigerians have had minimal or no improvement in their health status in the last few decades despite an increase in the number of health workers or professionals trained each year. There is rather a deterioration of health status shown by the increase in infant mortality rate (110/1000), under 5 mortality rate (190-205/1000) and maternal mortality rate (800-1000/10,000): one of the highest in the world,1 reduced life expectancy and a higher incidence of malnutrition, rapid dissemination of HIV/AIDS, and the emergence of other diseases. Malaria affects 300-500million people every year and 80% of these live in sub-Saharan Africa, 25% of whom will be Nigerians. Malaria kills 1-1.5million people every year – 90% of these deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa. About 3000 African children die of malaria every day and one African child is lost to the disease every second. Achieving the Millennium Development Goals may remain a mirage in Nigeria, except health care systems are able to offer quality services that are accessible to vulnerable population groups. This of course depends on availability of a well-trained, rationally deployed and sufficiently motivated workforce operating in an enabling environment. There is a need for quality undergraduate and postgraduate training and adequate incentives. Health workers’ performance, however, is also influenced by an array of other factors.2

All over the world Nigerian health professionals have distinguished themselves. The question then remains; why is the nigerian health system in such a deplorable state, with such a huge human resources? Environmental factors cannot be excused from the reasons responsible for the ailing health system. HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other communicable diseases are placing additional burdens on the health workforce. Almost two thirds (64%)of all the people living with HIV/AIDS are in sub-Saharan Africa including Nigeria.

Unfortunately the country is ill equipped to deal with the situation. For example, there is only an average of 0.8 health workers per 1000 population in Africa

In 2002, Nigeria had a nurse population ratio of 1: 20,700 people as against the 1: 1,000 which WHO recommends. To achieve the Millennium Development Goals, the minimum level of health workforce density require by WHO standard is 2.5 health worker per 1,000 people. In contrast there are 10.3 health workers per thousand in Europe and 9.9 in the USA.3, 4

The International Community seeks to address the health needs of the developing countries through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

This includes:

Ø Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Halve the proportion of people living on less than a dollar a day and those who suffer from hunger

Ø Achieve universal primary education

Ensure that all boys and girls complete primary school

Ø Promote gender equality and empower women

Eliminate gender disparities in primary and secondary education preferably by 2005 and at all levels by 2015.

Ø Reduce children mortality

Reduce by two thirds the mortality rate among children under five

Ø Improve maternal health

Reduce by three quarters the ratio of women dying in childbirth

Ø Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria and other Diseases

Halt and begin to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS and the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

Ø Ensure environmental sustainability

Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes and reverse the loss of environmental resources.

By 2015, reduce by half the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water.

By 2020’ achieve significant improvement in the lives 100million slum dwellers.

Ø Develop a global partnership for development

Develop further an open trading and financial system that includes a commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction- nationally.

Address the least developed countries’ special needs, and the special needs of landlocked and small Island developing states.

Deal comprehensively with developing countries’ debt problems.

Develop decent and productive work for youth.

In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries.

In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies – especially information and communications technologies 5

The MDGs can improve the health status of the country but this will only be a reality when three important issues are addressed viz: as brain drain, strikes and low moral among health workers.

The issue of brain drain

There are conflicting data on the exact number of Nigerian doctors outside the country. About 20,000 health professionals are estimated to emigrate from Africa annually.6 Today it is thought there are more Nigerian physicians in the USA and UK than in their own country .7 Though having the highest population in the continent, Nigeria alone looses more health workers than other African countries combined. Some estimates put the number of Nigerian doctors outside at one out of every five black doctor in the UK. In the US it is about one out of every 10. The story is also not different in other European and American countries 8 Another account estimates that over 23% of US physicians received their medical training outside the United States, with most (64%) coming from low or lower middle income countries. This group includes more than 5000 doctors from sub- Saharan Africa, which represents 6% of all doctors practicing in sub- Saharan Africa now. Almost 86% of these Africans practicing medicine in the United States come from Nigeria, South Africa, and Ghana, and the vast majority was trained at 10 medical schools.9 Data available on emigration of Nigerian nurses indicates that among 2000 African nurses legally emigrating to work in Britain between April 2000 – March 2001 about 432 were Nigerian.6 A 2003 statistic of registered nurses in the UK showed that Nigerian nurses topped the list.8

Studies focusing on why skilled health professionals emigrate have identified two broad categories: the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factor.10 11 12

a) Push factor –

Furthering their career

Improve their economic or social situation

Insufficient suitable employment

Lower pay

Unsatisfactory working condition

Poor infrastructure and technology

Persistent shortages of basic medical supplies

Lower social status and recognition

Repressive governments

Lack of opportunity for postgraduate training

Under funding of health-service facilities

Absence of established posts and career opportunity

Poor remuneration (Nigeria-based doctors typically earn about 25% of what they would have earned if working in Europe or North America.) 6 and conditions of service, including retirement provision

Government and health-service management shortcomings

Civil unrest and personal security

Lack of fulfillment in practice

b) Pull factor

Opportunity for further training and career advancement

Higher living standards

Better practicing conditions

More sophisticated research condition

The attraction of centers of medical and educational excellence

Greater financial rewards and improved working conditions

Availability of posts, often combined with active recruitment by prospective employing countries

Human Resources Development for Health

The health reforms required for achieving the MDGs demand a careful attention to making use of resources, especially human resources. This approach includes utilization of health care workers and their education and training and the evolution of a strategy that will improve the health system.

There must be a pragmatic approach that involves a more proactive management of the workforce. This will involve a change of attitude through orientation of the workforce. This change is not limited to a particular cadre but cuts across borders, affecting administrators, and health professionals, especially doctors, who are often in the leadership role. The new orientation will focus on enabling all health workers to see themselves as individuals responsible for the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of the health system.

Human Resources for Health (HRH) as a whole will require a close collaboration between the ministry of health, health care providers, colleges of health and educational institutions and professional associations. The individual strengths and capabilities of each group should be mobilized so that HRH issues can be tackled jointly.

Professional associations can make valuable contributions to strengthening, change of attitude and continuing education of health professionals, medical audit and monitoring systems.13

Much as the effort of the Federal Ministry of Health in her Health Sector Reform Programme (HSRP) is commendable, a more realistic approach is needed. It is not enough to outline programmes or talk shop about HSRP, NEPAD and MDGs. What is the impact on the common man, and what challenge is it to the average health worker? A highly motivated work force is needed to meet the challenges facing the Nigerian health system.

Policies are made without carrying along the health work force. If anything, the health worker who is in the frontline and is confronted by day-to-day challenges should be part of the policy-making process. As a matter of importance and urgency there is a need for a national health summit to address fundamental issues clogging the wheel of progress of the nigerian health system.

The following issues need to be addressed in order to find a solution to strikes and brain drain:

Ø Improved systems performance

Ø Capacity development

Ø Better remuneration packages

Ø Adequate work incentives

Ø Better training of health workers

Ø Personnel policy

Ø Create enabling environment for the provision of health services

Ø Management of data and performance

No doubt this reform will place a financial constraint on the government with regard to funding the health services. The Department For International Development (DFID) should make good its pledge to increase aid to Africa’s health sector. This has been implemented in Malawi (ranked 198 out of 198 by WHO), with 1.13 doctors per 100,000 [2003population] where a six-year 100million pounds programme to support Malawi’s health sector included investment in better training and higher salaries for doctors, nurses and other health workers.11 If this is replicated in Nigeria (ranked 187 of 191 member states in 2001), it will have a significant impact on her health system. During the G8 summit in 2005 the developed countries especially Britain demonstrated a renewed concern and determination to increase grants to solve the crisis the African health sector is facing.13 Countries like Nigeria can benefit from support World Bank, Global Fund and DFID to build HRH.

Brain drain has its pros and cons as it has for many enhancement of their personal and family economic fortune. The developing countries have served as training grounds for health professionals for many years. It is therefore disturbing when their potential contribution to health development in their countries is lost. Some of these doctors currently overseas may be willing to return to the country provided there is an enabling environment and adequate work incentives. Unfortunately some of those willing to return and help develop the health system have either been denied opportunities or subjected to discouraging accreditation procedures.6 Despite the scarcity of health professionals there is still high rate of unemployment. This has resulted in some new graduates waiting for years before getting places for internship or job placement. These factors will continue to encourage the emigration of health workers.

The way forward

The individual’s freedom should not be restricted as this amounts to human right abuse. Instead efforts should be made to retain health professionals by creating an enabling environment for medical practice in Nigeria.

Housing loan schemes should be provided, payable over a period of 25 years. This will go a long way to reduce the efflux of health professional

Car loans such that a doctor will be able to afford a new car.

Incentive for rural practice- health workers who practice in rural communities should be remunerated higher than those in the cities in order to retain them and attract more health workers. This will help reduce infant, under-five and maternal mortality rates. Instead of hiring foreign doctors who are paid in dollars despite their limitations in communication and inadequate exposure to tropical medicine, indigenous doctors should be recruited to such places with similar incentives. The hard currency paid one expatriate is enough to make five Nigerian doctors comfortable in any part of the country.

Regular in-service and short-term training courses on Basic Life Saving Skills (BLSS) and Advance Life Saving Skills (ALSS) could be organized on regular basis as Continued Medical Education (CME) for health workers in rural areas.

Recreational facilities can also be created in such rural environments as one of the incentives for health workers.

Consideration should also be made about the schooling of their children. This will open up the rural areas for rapid development as good schools and other social amenities will follow. This will attract teachers and businessmen to such areas.

Regular water and power supply should be ensured by way of sinking boreholes and power generators for constant supplies in areas that do not have electricity. However, electricity-supplying body should endeavor to extend their services to such areas.

We can develop friendly policies and create incentives that can attract or encourage the return of health professional based overseas.

Nigeria as the giant of Africa should be able to improve her health status with the staggering potential at her disposal. To this end Human Resources Development For Health should be given adequate attention to reduce the impact of brain drain in the health sector. Hence the noble goals of the MDGs can be achieved when the three tiers of government in this country, the private sector, Non-Governmental Organizations and the International Community realize how much they owe the people of Nigeria - an efficient, effective and quality health care system that works.

To realize this noble goal a National Health Summit that will bring together all the key players in the health sector to brain storm on the issues raised above and find an enduring solution to the challenges facing the sector is being organized.

The Millennium Development Goals are achievable and realistic.

References:

1. Habte D, Dussault G, Boostron E, Pearson B. Education of professionals and the human resources crisis in Africa: Medical Education Resources Africa (MERA). March 2003, pp. iv-vi.

2. Okeahialam T C. The Nigerian child and the Millennium Development Goals. 37th Annual General and Scientific Conference: PANCONF 2006, Jos Nigeria.

3. Addressing Africa’s Health Work Force Crisis: An avenue for action, Abuja Declaration

4. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. Report from Consultation in Oslo 24th – 25th February 2005.

5. WHO Millennium Development Goals. Report of Secretary –General. A57/270 (31 July 2002)

6. Stilwell B et al. Managing brain drain and waste of workers in Nigeria. Bulletin of the World Health Organization

7. Pearson B. The brain drain: a force for good? Medical Education Resources Africa (MERA). January 2004)

8. Okumephuna Chukwunwike. The Ever Green Story of Brain Drain. USA/Africa Dialogue, No 669: Brain Drain (The Guardian, Thursday, May 5, 2005)

9. Hagopian A, Thompson M T, Fordyce M, Johnson K E, Hart G L. The migration of physicians from sub-Sahara Africa to the USA: measures of the African brain drain. www.human-resources-health.com/content/2/1/17

10. Chen L C, Boufford M. Fetal Flow – Doctors on the move. New Engl J M 353;17 Oct. 27 2005, pp. 3850.

11. Ahmad O B. Managing medical migration from poor countries. BMJ vol 331. 2 July 2005, pp 43.

12. Fifth-Seventh World Health Assembly [22 May, 2004] A57/VR/

13. Alwan A, Homby P. The implication of health sector reform for human resources development. Bulletin of WHO vol. 80 no. 1 Geneva.

14. Loss of health professionals from sub-Saharan Africa (Lancet vol. 365 May 28, 2005).

Friday, January 26, 2007

$300million Lifeline for Primary Healthcare Development in Nigeria?

This is good news: that is, if you are reading this post from Australia, Europe, North America, e.t.c where most government policies immediately translate to projects that directly impart the people. The average Nigerian is skeptical, if not out-rightly cynical when such pronouncements are made since many have mastered the art of siphoning public funds. It is called refined thievery!

We find that the most successful health initiatives are those managed by private enterprises that are goal-oriented and result-driven embracing sustainability because of its direct relationship to their reputation. These enterprises crave for and incorporate the input of community. Poor communities cannot abandon the quest for improved health outcomes to government alone especially in societies with inept, mediocre and pathological governance as described by Paul Farmer, the renowned physician, Harvard researcher and medical anthropologist (founding director, Partners In Health. www.pih.org.) in his Pathologies of Power. Poor communities must harness their resources, constructively engage government and ensure that policy papers such as the one just produced by the Nigerian government about primary healthcare development come to fruition. It is an error to sit and wait for the spontaneous realization of primary healthcare development: it will never happen without concerted, collaborative efforts.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Light has come to Arusha!

Thank you, Gillian, for your comment on my last post and for urging me to keep on writing. Your post has given me a renewed impetus to stay the course.

I have seen your blog. It reveals the great work being done to impart the lives of these disadvantaged kids in Arusha. Small efforts make a lot of difference. Only time will tell what difference you have made!

It is worth visiting www.schoolstjude.blogspot.com to see what is being done for 850 kids from the poorest families at the School of St. Jude in Arusha, Tanzania. The photograph shows a nearly completed class building taken in December 2006.